ODI exhibition of new artworks which explore truth and data: a hot-pink ‘puppet-robot-hybrid’ who wants to chat, Google’s mis-translated versions of William Blake’s poem Jerusalem and a pinball machine offering a neurodiverse experience of the city.

Three new artworks will be exhibited at the Open Data Institute to raise questions about the role, veracity and impact of digital duplication through the curatorial theme Copy That?

Mr Gee, Alistair Gentry and Ben Neal working with Edie Jo Murray and Harmeet Chagger-Khan, were commissioned by the ODI’s Data as Culture art programme to explore data, both critically and materially.

Data as Culture was the first programme launched by the ODI when it opened its doors in 2012. The programme aims to create conversations around and with data, inviting opinions from across society and making data accessible to everyone.

Copy That? considers what happens when we copy data and what gets lost or gained in translation. Art can enable us to consider how technology helps us understand the world, but also how it affects our autonomy.

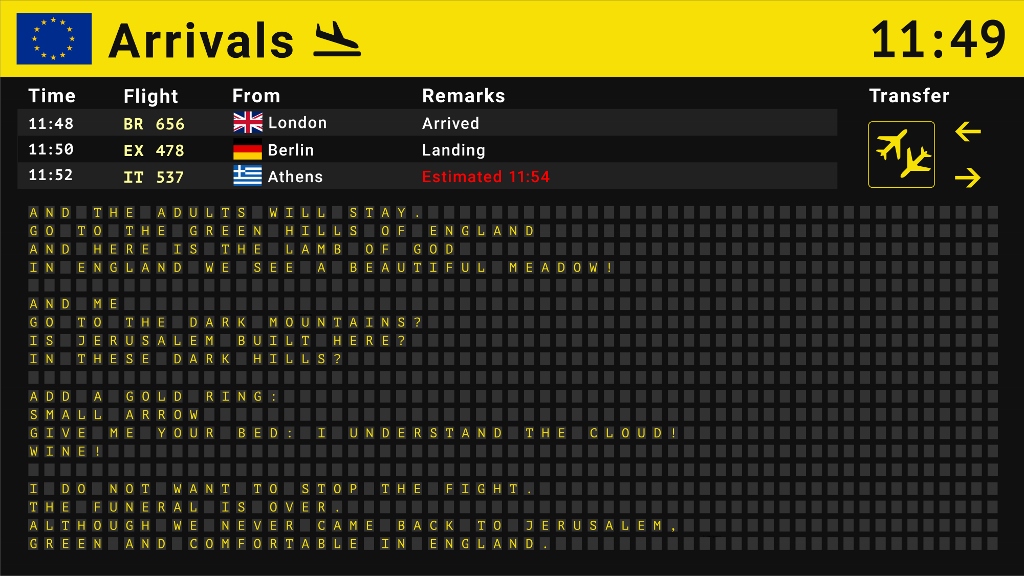

Performance poet Mr Gee‘s Bring Me My Fire Truck seeks to artistically explore the ‘soul of Brexit’ through William Blake’s poem Jerusalem. Created as a text piece symbolically displayed as a departures board at an airport, this artwork sees the poem translated from English through the 23 other official European languages and Welsh, using Google Translate. Meaning deteriorates and reforms according to different algorithmic interpretations, assumptions and corruptions. As it cycles through, it becomes a hybrid version of itself, at once funny and disturbing, ever changing its perception and its point of view.

Mr Gee says: “I’ve always been a big William Blake fan, the hymn that we know as Jerusalem is actually a poetical extract from a longer piece that he wrote called Milton. As a poem, Jerusalem is quite a self-examining and fantastical exploration of the soul of England. I wanted to represent people’s immigration fears through the changing of the poem and this the re-translation brings forward a fresh insight, sometimes it seems hilarious, sometimes it’s nonsensical, sometimes it’s sinister.

“Data is the past, present and future and we have always used it to evaluate our position to try and make informed predictions for our advantage. We shouldn’t run from it, we should embrace it, because the ancient need for the interpretation of an astute soothsayer always remains the same.”

In his work DoxBox Trustbot, artist Alistair Gentry has created a hot-pink puppet-robot-hybrid to test how much trust we place in online apps and services. DoxBox questions if it is worth disregarding online security and data rights, in order to easily access services online. It wants to find out how free or cautious we are with data about us, drawing our attention to the many data versions of ourselves that might be created online.

Alistair Gentry says: “I’d like people to think about whether their trust in online service providers is justified once they know a bit more about what’s really going on behind the scenes. The same tools that can make our lives easier and more fun can also be used to oppress, monitor and deceive, sometimes simultaneously. But in all these scenarios, there are usually things we can do to empower and protect ourselves.

“What surprised me about my research at the ODI was that the data we volunteer is just the beginning. There are vast quantities of extremely valuable data generated around all of our online activities without us knowing it, and then yet another layer of data that is inferred from it. My research led me to want to satirise how we have become a ‘product’ to the companies that create the apps as the most valuable thing about us has become our data.”

In Mood Pinball, created by artists Ben Neale and Harmeet Chagger-Kahn, players are taken on a sonic journey of the dreamlike city-scape world of neurodiverse artist and collaborator Edie Jo Murray. Navigating the digital version of a traditional pinball machine, the player’s goal is to collect noise level data from different locations, which have an impact on Edie’s mood.

Heightened noise sensitivity is often experienced by people living with neurodiverse variations, such as autism or ADHD. Accessing data about noise levels in public spaces is difficult, so the noise data in this artwork has been synthesised by computer scientists at Southampton University, following artist-led workshops with neurodiverse people. The workshops revealed how important it is for many neurodiverse people to be able to plan their daily lives around noise-friendly or unfriendly environments. The piece invites us to consider how collecting and sharing true data about sound levels in cities could help all of us find our comfort zones.

The Mood Pinball artists say: “We wanted to playfully re-imagine how city-wide data could be used by an individual or explored by playing a game. Mood Pinball was created from a neurodiverse perspective, focusing on noise levels in an urban environment and the effect they can have on wellbeing. Players encounter a large, bright, highly stylised pinball machine with a synthesized dataset buried deep in the heart of the code. The visual style of the game is based on the analogy that autistic people can feel like aliens on this planet, and through engaging with the game players explore and discover an alien landscape via the data readings they encounter”

See the new artworks at the ODI, London from 5 February 2020 (by appointment) as part of the Data as Culture research and partnership season for 2019–2020, Copy That? Surplus Data in an Age of Repetitive Duplication.

xxx

Dates: 5 February 2020 to 30 June 2020

Opening times: 10am to 5pm by appointment only email dac@theodi.org to book

Venue details: Open Data Institute, 65 Clifton Street, 3rd Floor, London, EC2A 4JE