I’ve been fascinated by the funny world of cartoons since I was very little. As a child, it was Mickey Mouse & friends. I still remember – and I’m not embarrassed to say – the high pile of cartoons in the loo, a perfect way to spend the time there.

Then I grew up, and I’ve discovered another type of cartoon, which is presenting witty and subtle criticisms towards society, making people laugh and think at once. I’ve started to appreciate this genre for its black humour; for its blunt, straightforward, and sarcastic images and jokes.

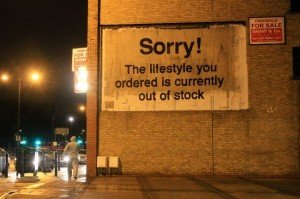

Nowadays, the art of graffiti and that of cartoon seem to go together quite well in the way they both carry underlying political messages. If you’re familiar with Shoreditch, you know that this is the perfect place to see street art and dark humour merging together. Not to exaggerate, but pretty much every corner seems a comic strip, and every wall is sprayed with provocative images and messages.

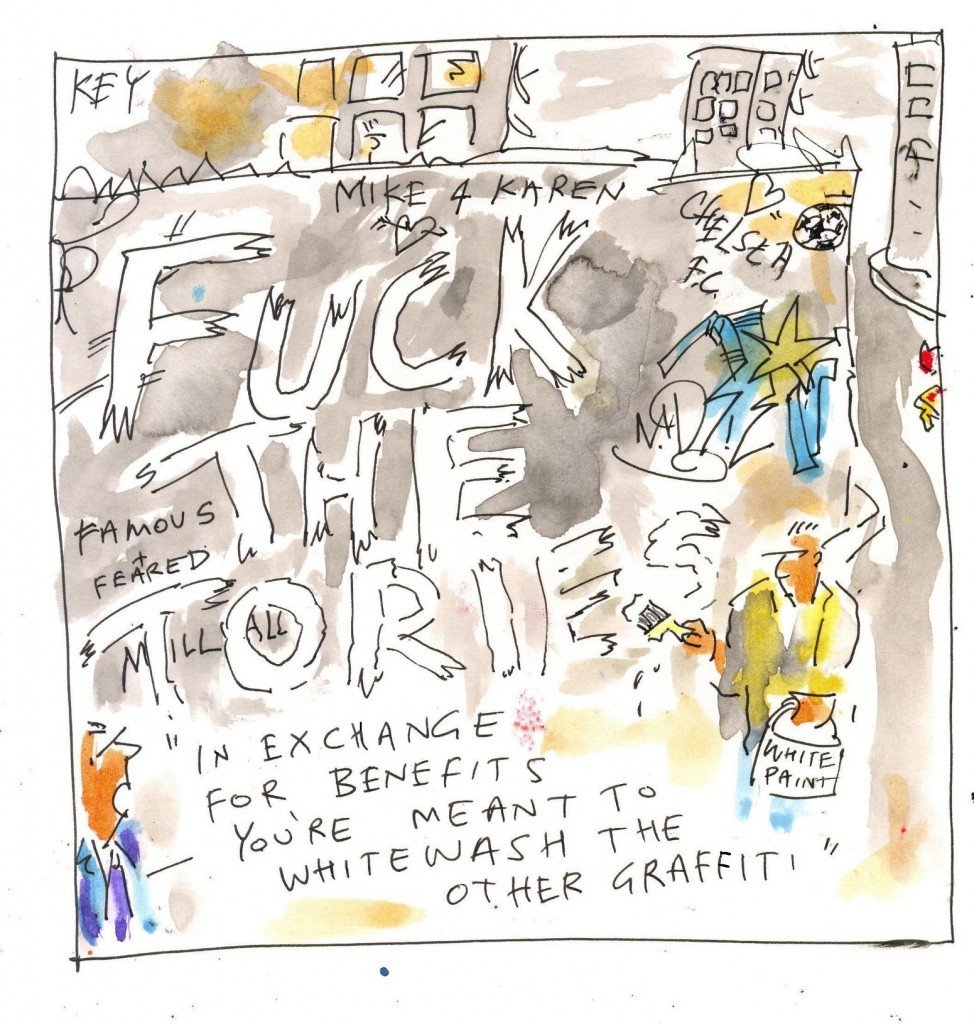

Though, to be a keen reader of cartoons and a habitué of Shoreditch doesn’t make me an expert. Instead, it does arouse my curiosity: and this is how this interview with Simon Key, a London based cartoonist working for the satirical magazine Private Eye, came about.

Q. How did you get started into cartooning?

A. It all started with my enthusiasm for Asterix & Obelix… All jokes aside, I remember I always drew a lot as a kid. At about twelve, I became a very big fan of Spike Milligan, one of the most influential figures in the British comedy scene and to my mind the Godfather of British anarchic humour. I loved his cartoons and wild jokes. However, what really kicked off my cartoonist career was Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson, illustrated by Ralph Steadman. I found its dark and amusing take on ‘The American Dream’, the astonishing writing and the spectacularly grotesque drawings, absolutely brilliant and a great inspiration. After doing different drawing jobs and exhibitions, I’ve been mainly doing political cartoons in the last ten years, and to have a chance to some kind of voice in the political arena is great.

Q. Political cartoons have always played a key role in British culture, and more recently also graffiti art has gained a great stature. What are the similarities between them, when it comes to satire and their impact on people?

A. In the British context, the graffiti artist who has raised street art to a new level is Banksy. His political and social commentary are an inspiring public force, similar to that of political cartoons. They both can mock, and at best scare, politicians and centralised power. However, they differ in the way they enter peoples’ lives. Of course, a cartoon is something you find in a newspaper, and you’re not forced to look at it. You can just quickly turn the page. With graffiti, instead, you can’t help but look at it. Whether you like it or not, street art is much more intrusive than cartoons in everyday life.

Q. Should there be complete freedom of expression for political cartoon and graffiti?

A. At the milder end of the spectrum, editors and newspapers are fully aware of the risk of getting into trouble, with say, libel, and being sued in court. But at the darker end of things, in the modern age, cartoons of Mohamed or jokes about Israel can inspire global rage, murder and terrorism, so you have to be careful. The freedom of press is an undeniable right … but still, this is a very tricky issue. Some jokes, to my mind, are completely unacceptable, like fascist, racist jokes designed to spread hatred. We have witnessed how powerful and dangerous the impact can be on society, and we don’t want to repeat what happened in the past.

Q. Let’s go back to street art, and that of Shoreditch in particular. What are your closing thoughts on the scene?

A. Like I said, I believe street art could be quite intrusive, almost threatening and aggressive in a way. Gangs can use them for marking their territory, for instance. Yet, the other side of the coin is that graffiti can actually give a sense of positive urban, of belonging to a particular community. And I think this is probably the case for much of the works in Shoreditch.