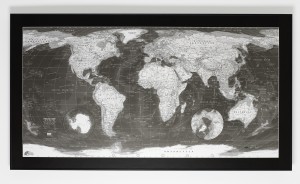

As a matter of fact, it is impossible to portray the planet as a flat image. The only totally correct representation of the world is indeed the globe, which means that cartographers have to distort the sphere in one way or another. This is perhaps what makes cartography a controversial and fascinating discipline, oscillating between art and science, subjectivity and objectivity, fantasy and reality.

Simply, maps aren’t paradigmatic. But because we have been educated with a specific projection of the world, we generally seem to trust them as a real, accurate depiction of reality. Here we explore the alternative (as such, to a certain extend eerie) image of the planet that the East London’s Future Mapping Company gives us. We caught up with the founder of the company, Marcus Kirby, to talk about the history of cartography and how maps work politically, influencing our understanding of the world.

Q. Could you tell us something about your background? How did you get started in the art of mapmaking?

A. I’ve always loved maps. My parents used to take me to the Lake District on walking holidays and my dad would buy me a map of the area we were walking in. I would mark the routes we walked on it using fluorescent highlighter pens – very geeky! It was at this point I fell in love with topographic maps, the beauty of the detail and how they represent the land in which we live on a printed piece of paper.

Strangely I never considered a career in cartographic design. Having finished my A-levels, I found myself taking suits apart during a foundation course in art and design; the next thing I was doing was a fashion degree course. I worked in tailoring with Timothy Everest for about 5 years, learning the ins and outs of this craft, but more importantly I got a fantastic view of how to reinvent a struggling craft. Tim’s challenge was to remove the stuffiness of the tailored suit from being a preserve of those who felt comfortable within the surrounds of Savile Row.

My desire was to set up my own company and my thoughts soon turned to maps.

Q. To quote the Telegraph Magazine, “The Future Mapping Company has revolutionised the traditional wall map”. How does your mapping of the world differ from the conventional one? What makes your representation of the planet so “alternative and thought-provoking”?

A. I began looking at the world maps on the market and soon found that they all seemed to conform to the same graphic style. You will remember from your school walls – patchwork political map in soft pastel tones. It was at this point I decided to have a go myself, to design an image of the world in which we live that you would want to put on your wall as a piece of graphic art.

Our first line of maps was called Future Maps, (bold and brash I know!), these utilise an equal area projection, an alternative vision of our planet that shows countries in their correct proportional size. The Mercator map projection that we remember from our school days was- believe it or not- developed in 1569 as a navigational tool and whilst it is fantastic for this – getting the coastline of countries correct in respect to angles and distances of travel – the sizes and surface areas of the countries closest to the poles are hugely distorted. So the old folklore that our beloved Blighty is too big on a world map may be true, but nowhere near as distorted as Greenland, which is 550% too big on a Mercator projection map!

By contrast, our map shows Africa as the dominant continent, Brazil is as big as the USA, Russia is no way near as big and scary as it used to be, and Europe is not positioned in the middle of the map. It is really quite different and does cause people to stop and question when they see it.

From a design point of view we wanted a harmonised world view, still showing country borders but not reinforced with the use of the patchwork system; so we graded the colour through countries and continents, leaving neighbours only a shade away from one another. And for the print we opted for a 6 colour lithographic print on a top quality coated paper with a gloss varnish applied to the landmasses, graded silver metallic seas and a bold modern sense of colour. They went on to sell in some very cool shops worldwide.

Q. According to Peter Barber (Head of Map Collections at The British Library), “The artistry of maps is seductive and like the teaspoon of sugar that helps the medicine go down, tries to persuade us to swallow a particular political message.” To what extent do you believe that cartography can shape and distort our belief of the world? Would you describe maps as a strong political instrument?

A. Mercator finished his projection in1569 and it was still in my school atlas in the early 1980’s. I remember thinking how big Greenland, Canada, Russia and the USA were and how neatly the UK was positioned in the middle of them looking rather proud and Empirical-like! All these Northern hemisphere countries I later found out were so much larger on this Mercator map than their actual size. When I found out that Greenland was 550% too big I was astounded. The equator isn’t even in the middle of the map!

It really comes down to this; our earth is a sphere, spinning in space. There is no truly correct way of flattening a sphere, which means that there is no truly correct way of representing the earth as a flat image. It is all open to interpretation and well, of course political influence.

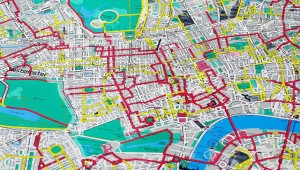

Q. After mapping the World, Europe, as well as the cities of New York and London, what does the future have in store for you and your business?

A. It can take us up to 6 months to make a city map at street level, just imagine of the work created by changing a font! So we only manage to tick off a couple of maps of our very long wish list each year. We love maps and we want to continue working with the printed piece of paper and to hopefully create long lasting and inspiring images that people want to put on their walls.

http://www.futuremaps.co.uk/