Where do icons go when they die? When music, film and culture mean so much more to us than anything organised religion can offer, what happens when the individuals who embody those things so intensely, finally come to pass? How do we venerate them with enough significance to show how much impact they had on our lives? The Catholic Church seemingly has the process down pat when it dishes out sainthoods for services rendered, but us consumers and worshipers of pop culture must seek out alternative means of posthumous reverence. How do we remain as close as possible to our idols in their absence?

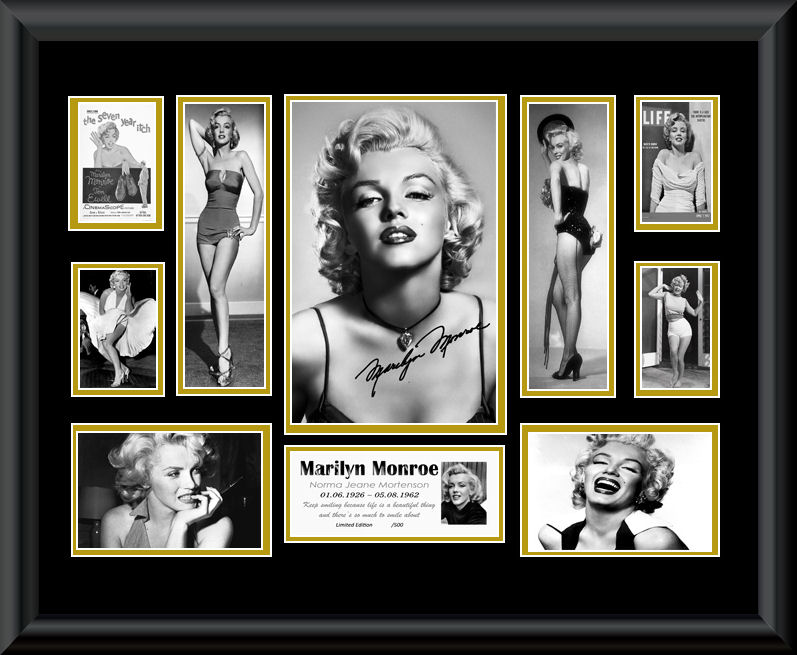

Enter the weird and wonderful world of celebrity estate auctions. On the 17th of November 2016, Beverly Hills based auctioneers, Julien’s, sold what they themselves claimed to be a ‘once in a life time collection’ of Marilyn Monroe memorabilia. The auction featured some absolutely iconic pieces from her career, least of which was the dress that was worn whilst singing ‘Happy Birthday Mr. President’ to John F. Kennedy in 1962; price tag of $4.8 million.

But what is really interesting is just how banal the items got from then on in. If it tickled your fancy (and for the right price of course) you could have purchased anything from one of Monroe’s empty lipstick canisters, to her hairbrushes, cake tins, cookbooks, ash trays or paperweights. It was all there for taking.

So what is the appeal of owning a generic ashtray that once sat idly in Marilyn Monroe’s home? What possesses the public to pay such staggering sums for such prosaic items? Is it purely for the bragging rights of being able to say to dinner party guests, as they stub out their cigarettes, ‘Hey you know that ashtray right…’ Or is it something deeper?

Taking a look through Julien’s other auctions for the year, it’s possible to see that their entire business model is based solely on the desire from the general public to own artifacts and memorabilia from various forms of celebrities. The auction prior to Monroe’s for example, titled Icon’s and Idols, contained note books and band equipment belonging to Prince, the personal property of Frank Zappa and intimate correspondence between Audrey Hepburn and her family.

The demand even appears to reach the very top echelon of the market where back in 2011 the London based auction house, Christie’s, managed to secure the rights to the sale of Elizabeth Taylor’s vast estate. More recently even, Sotheby’s hosted an auction of the late David Bowie’s personal art collection. So again, where does this demand for the personal property of celebrities come from?

This idolization of objects as some form of connection to a higher order is nothing new. Societies have sought out tangible connections to greater worlds for time immemorial. After all, do not most religions lay claim to having some sort of relic or artifact that can be traced back to the very foundations of their inception? Some bone supposedly belonging to the finger of saint, locked away in a gold box behind an altar? Some rock some one claimed to have seen fall from the heavens that they lodged into the scepter of a priest? Some cloth they claim was once wrapped around the face of a prophet, that now sits framed and protected in a vault? The fact that these items have even a tenuous association to something as transcendental as one of the gods, or even the God, of these religions, endows them with a particular power to be able almost manifest the previously un-manifest-able.

So really for a culture that has slowly moved away from the idolization of organised religion and edged more to the idolization of one another, it seemed only a matter of time before we gravitated towards physical items that gave us the impression we were not within the presence of just an ashtray but of our idols themselves.

Understandably, we can assume that not all people who intended to partake in Monroe’s auction that day were seeking some sort of spiritual enlightenment through a purchase. They may have, after all, just really needed an ashtray. But for those that were, ultimately what these objects come to represent is the almost literal manifestation of a myth. We cannot see Marilyn Monroe anymore, we cannot meet her, we can only learn about her from others. So when we are in the presence of an object that was once in her possession, be it a ball gown or an ashtray, the myth suddenly becomes fact. And who doesn’t want to see fairy tales come true?

The estate of deceased celebrities will forever be making headlines (especially now given the events of the past year.) Vast fortunes, coupled with tenuous family relations and complex business partnerships will always bring out the worst in people. Throw some grief in there for the death and it’s a fatal cocktail of emotions that is ripe for a never-ending stream of horrible magazine covers and poorly worded news titles.

But the decision for families to allow the most intimate items of these idols to be released into the world works wonders for the legacy of the deceased. Our idols who once seemed so untouchable and so unattainable, are brought back down to earth and back into our lives resulting in the fairy tale of their monumental success and fame appearing all the more achievable to us all who were left behind.