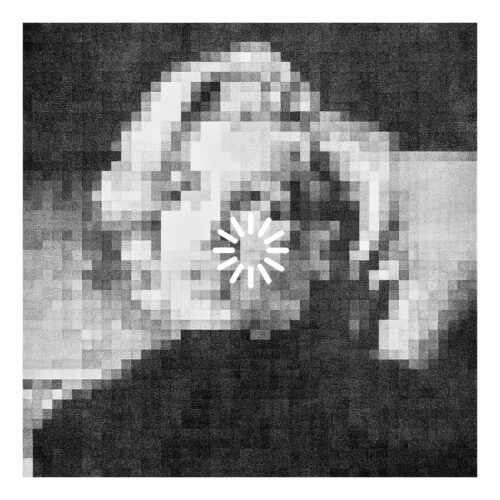

From blueprints to pixels, MAESTRO has seamlessly transitioned from the world of architecture to a strikingly precise artistic practice. With a meticulous approach rooted in structural planning, his work explores the intersection of physical and digital realities. Best known for the pixelated loading series, which presents iconic figures in a state of perpetual incompletion, he challenges our fast-paced digital consumption while reimagining history through a contemporary lens. In this conversation, he discusses how his architectural background informs his artistic vision, the cultural influences that shape his work, and his evolving fascination with the future of digital art.

Your transition from architecture to art is intriguing. How has your architectural background influenced your artistic approach, particularly in terms of structure and composition?

Architecture has definitely honed my precision and attention to detail. I also think it influences my need to plan things beforehand—I don’t improvise so much as execute my creative ideas. For me, creativity is in the mind not in the material. I prefer to have near-complete control over my chosen medium. My knowledge of certain architectural design softwares has also been useful in the brainstorming process, and in the construction of the augmented reality “worlds” that complement each of my analog pieces.

While my art critiques our present obsession with digital consumption, especially as a way of relating to the past, I also see each pixelated piece as a blueprint for a future digital world. Just as each iconic “loading” image or figure represents a broader configuration of meaning (Marilyn Monroe, for example, is a figure who means many things to many people), each physical configuration of pixels has the potential to become its own digital landscape through augmented reality—a potential that reflects the fluctuating uncertainty of our digital future.

The pixelated “loading” series presents iconic images in a state of perpetual incompletion. What inspired this concept, and what commentary are you making about digital consumption and imagery?

Digital culture means we never really look at things for long. We over-consume images and have come to expect immediate access and high-definition from all our media. Among other things, I see my “loading” pieces as a means to slow down and a longer look—as a playful way of questioning our current culture of rapid insatiability. Not too long ago, short of seeing the Mona Lisa in person, we would only have had access to her via a poor-resolution, black-and-white photograph in a column of the newspaper. The access we have to history and culture today is exciting, but it is also a new kind of illusion. We can record the present like no other time in history, but the past (even the near-past) feels more elusive than ever, and the future is always changing. This series is engaging with that.

Balancing time between Spain and the United States, how do the distinct cultural environments impact your creative process and thematic choices?

I grew up in Spain, where in general I find we are fascinated by American popular culture. As a young boy, I was constantly receiving impressions of American icons and events through a filtered lens, and I think this eventually led to my re-examination of that subject matter in my early work. Now that I live in California and visit Spain, I find my fascination traveling the other way. People often contrast the beauty of Europe with the excitement of the States, but I find elements of beauty and excitement within each culture.

I would say that a consistent theme of my work is an interest in the iconic moments and figures of human history, including those most likely to become historically iconic given their status in the present. I’ve drawn Taylor Swift, for example, because I think she is likely to be seen in the future as the Frank Sinatra of our times, and there are many other figures who interest me for the same reason.

Your work often features a monochromatic palette with black ink on white paper. What draws you to this minimalistic aesthetic, and how does it enhance the narratives within your pieces?

When I first immigrated to the United States, my life was very chaotic and uncertain, and I had limited space within which to work. Black pen on white paper was an economically viable, clean, and simple way to begin, and I quickly found that it enabled the precision and elegance that I value most in art. I see the black-and-white aesthetic as something that removes distractions, keeping things timeless, while pen on paper results in a velvety, textured look that feels provocatively nostalgic. It also forces the subject matter to stand on its own, which I feel strongly about in my work. Ultimately, I think my passion for pixels has developed overtime alongside my fascination with minimalistic storytelling—what is the minimum amount of information needed to make an iconic subject recognizable to a viewer?

Looking ahead, what projects or themes are you excited to delve into, and how do you see your art evolving in the coming years?

For the time being, my future is all pixels. I would love to do a series of pixelated drawings that examine Spanish popular culture and history. My ultimate dream is to have an exhibition of that kind in my home city of Valencia, and to design the “Falla Municipal” for our annual cultural festival. I’ve also recently produced my first sculpture, a pixelated version of the Venus de Milo, so I see that side of my work continuing to develop in the coming years. Should the opportunity arise, I would enjoy designing pixelated versions of iconic American awards, such as the Oscar or the VMA’s Moon Man.