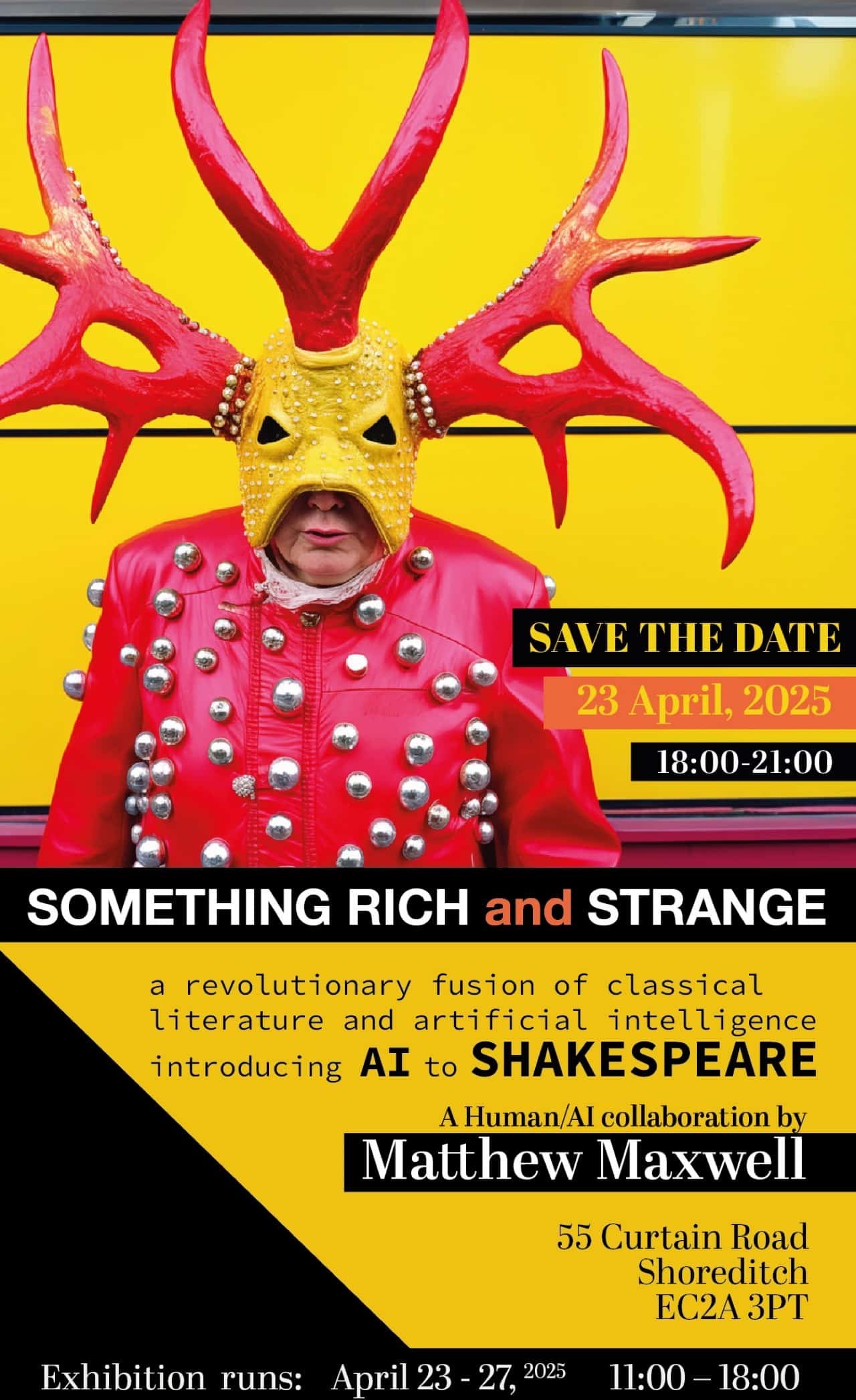

Shakespeare’s world collides with AI in Something Rich and Strange, an immersive exhibition by Matthew Maxwell, opening on April 23—Shakespeare’s birthday—in Shoreditch. Maxwell, an award-winning creative director and AI researcher, merges the timeless narratives of Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream with cutting-edge Generative AI. In this interview, he discusses the inspiration behind the project, the role of AI in artistic creation, and how technology is transforming storytelling.

How did the idea for Something Rich and Strange come about, and what inspired you to merge Shakespeare’s world with AI?

Surprisingly enough, Shakespeare and Generative AI (GenAI) have a lot in common, despite being separated by 400 years.

They represent two examples of Large Language Models (LLMs): AI as a computational construction, Shakespeare as its cultural equivalent. Both boast an awesomely vast vocabulary and the ability to add to it. Both use words to paint pictures. Both challenge old conventions and promise new forms and artistic opportunities that seem better equipped to describe the world they find themselves in. Both propose new ways of understanding life and the experience of being.

Shakespeare’s words had to work hard. They needed to transport audiences to Italian palaces and grim English battlefields. On the bare-bones stages of Elizabethan theatre, words alone had to evoke enchanted islands, magical forests, taverns and slums. His audiences lived in an age when visual imagery was rare and crude. But his words had the power to light the touchpaper of imagination. And the persistence of his canon – the continuing relevance of those words – demonstrates their lasting poetic potency.

Generative AI does the same. I invite it to examine his poetry as prompts and return them as visual and audio evocations. Obviously, artists and composers have done this for centuries. But GenAI adds another layer. Instead of simply illustrating the characters and themes, it twists and teases them in ways that often defy obvious logic; filtering them through an imaginative process that applies algorithmic logic.

AI is often seen as a disruptor in creative fields. How do you view its role in artistic expression, and what excites you most about integrating Generative AI into your work?

I’m excited to have these shiny new toys to play with. What’s fascinating about GenAI is the way it can reach out – like an octopus – and gather-in elements that are not obviously connected. It will happily mashup styles and media and it’s happy to keep experimenting and combining with inexhaustible patience.

And because it doesn’t have any lived experience to tell it “That’s not possible!” it’s not inhibited by reality, the way that we are. Making art is often about finding the spaces hidden between conventional ways of seeing the world. Because GenAI doesn’t hold those preconceptions (or doesn’t seem so confined by them) it offers a great way to slide into those gaps and explore them.

On the flip side, that very effortless dexterity poses problems of its own. I think one threat this technology poses to artists is the degradation of skills that might turn out to be essential. For example, contemplation of a developing artwork is an important part of the creative method. The slowing down of time, the “watching paint dry” is the temporal space where deep thinking occurs. As GenAi spits out version after version, generating in seconds what used to take hours or days or years, it becomes harder and harder to actually see any of them. Something gets lost in the velocity of production.

This is always a risk with labour saving technologies. Our ancestors took took millions of years to evolve the ability to navigate – to observe the landscape and build up a mental map of it. But now that I have Google maps and satnav, I no longer need to deploy this. I can already feel my ability to navigate fading. I’d be sorry if GenAI’s productivity cost me the ability to Look slowly and carefully in the same way.

Your exhibition is opening in Shoreditch, close to the original site of Shakespeare’s Curtain Theatre. How does the location add depth to the experience?

‘Something Rich and Strange’ will be shown at 55 Curtain Road in Shoreditch, the epicentre of the birthplace of Shakespearean theatre, midway between the two venues where his company performed at the end of the 16C. By placing the experience in this location, I hope to access something of its ‘Genius Loci’ (the persistence of character); the ineffable quality that connects creative behaviour through time. The essential personality of place that fosters the timeless, disruptive, creative behaviour that the location exhibits. Shoreditch has been a creative nexus for centuries, there must be something about the place that acts as a catalyst for that.

You describe AI as both a muse and co-creator. What has the collaboration process been like between you and the technology, and how much control do you feel you have over the final artistic outcome?

I describe the process of making art in this way as ‘Creative Cybernetics’. Cybernetics looks at how a system notices what it’s doing, compares it to a goal (or desired state), and makes adjustments to stay on track. Like a thermostat which senses room temperature, compares it to the desired setting, then switches the heat on or off to maintain that setting. I work with GenAI in the same way. I have a desired state in mind, but the environment that GenAI provides is a complicated and fluid one. It may struggle to understand what my goal is and produce suggestions which deviate from it, or it may come back with suggestions I hadn’t considered. The guiding principle is uncertainty – GenAI can’t be sure what I’m trying to achieve, and I can never be certain why it is making the decisions it does. That openness-to-opportunity is an exciting place to operate as an artist.

Shakespeare’s plays have been reimagined in countless ways. How does AI allow for a completely new interpretation of his iconic characters and narratives?

It’s true, these plays, poetry, themes and characters have provided inspiration across the centuries. It seems they provide a very useful playbook for what it means to be human. In an episode of Star Trek, captain Jean-Luc Picard uses a scene from Henry V (which probably premiered at the Curtain) to coach the android Data on human values and behaviours. Data is puzzled why the king is displaying weakness an uncertainty, Picard explains that such emotional nakedness shows how empathy is generated, and the bond between the leader and the led is strengthened, counterintuitive as it may seem to the android’ very rational thinking. I’m kind of doing the same thing – revealing some of the ineffable messiness of being human to AI’s training data, hopefully helping it to understand us better.

With the rise of AI-generated art, there are concerns about authenticity and originality. How do you respond to critics who argue that AI undermines traditional artistic craftsmanship?

I’m actually at the SXSW conference in Texas at the moment. This is a massive meetup of tech and culture, so questions of authenticity and agency are very much on the agenda. I’ve heard a lot of opinions, from legal issues of IP to fears about skill degradation and the loss of agency. One interesting analogy was presented by the musician Will.i.am. (from the Black Eyed Peas). He pointed out that the two pillars of the music industry are publishing and recording. Historically, Publishing reflects how classical music is a performed art, while Recording is constructed in the studio for mechanical distribution. He suggests there is a third pillar necessary, which can acknowledge non-human creativity. But quite what that look or sound like, nobody seems very sure.

Your background spans fine art, film, TV, and interactive media. How have these different creative disciplines influenced the way you approach this exhibition?

This body of work draws upon all of them. That is what’s so exciting about GenAI agents – it provides tools to reconcile so many different strands of thinking and creativity. For example, I use a musical AI agent to generate songs using Shakespeare’s lyrics, then create characters to sing them. I can make my ‘actors’ dance, and I can design the costumes they wear. Cinematic scenes that I could imagine, but never afford to stage, are now possible. GenAI is a kind of imagination prosthesis – to not use it would be like not wearing glasses to enhance my eyesight, or going barefoot because shoes aren’t ‘natural’.

Looking ahead, how do you see AI continuing to shape the future of storytelling and artistic expression? Do you think it will become a staple in contemporary art exhibitions?

Of course. It offers new creative possibilities, and artists have always been up for that. We can cite Shakespeare again here – the flowering of theatrical language in the Elizabeathan era provided him with a rich framework to build upon. The ‘natural language’ forms he used were new and exciting for audiences and their enthusiasm made him a rich man. Whether it will become a ‘staple’ is less certain, as the speed of change makes it very difficult to describe it as a single, unitary entity or technique. But as AI in general continues to permeate every aspect of our daily lives it woul be pretty remiss of artists not to see what can be done with it, to reflect critically on it, and absorb it’s powers and potential into how they work and the work they make.

xxx

Immersive Experience in Historic Shoreditch

Located at 55 Curtain Street, EC2A 3PT, the exhibition will offer visitors a multi-sensory experience where tradition meets modernity. The gallery’s proximity to the site of Shakespeare’s Curtain Theatre, where the Bard wrote and performed from 1597 to 1599, adds a layer of historical significance to the event.