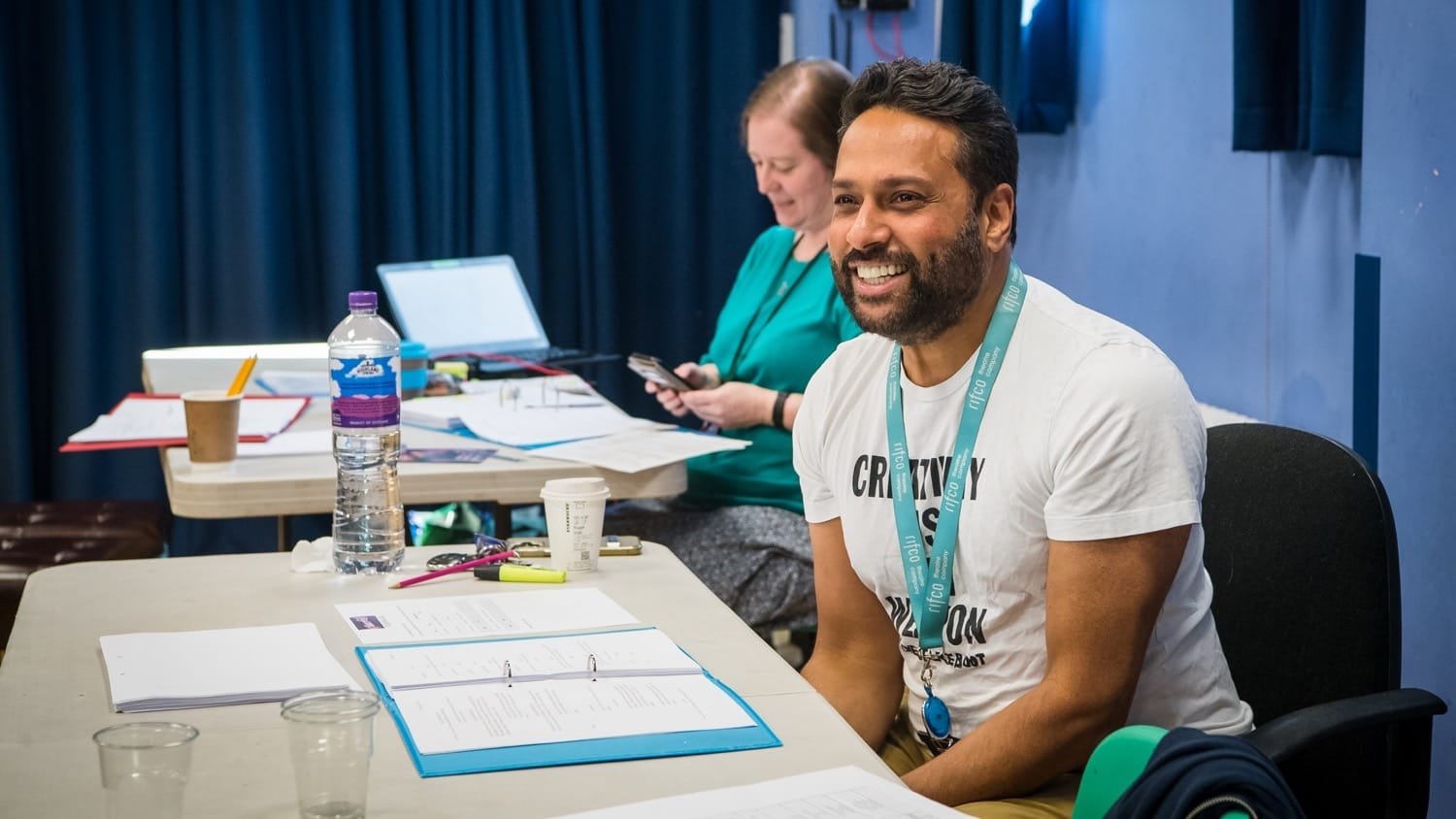

Artistic Director and Chief Executive of Rifco Theatre Company Pravesh Kumar MBE has spent his career amplifying British South Asian voices, but The Indian Army at the Palace marks a milestone even for him. For the first time, these stories are being performed on the very grounds where Indian soldiers once stood, turning Hampton Court Palace into a living site of remembrance, identity and cultural reclamation. Through intimate storytelling, community collaboration and a powerful symbolic shift from poppies to marigolds, the production reframes a chapter of British history often overlooked. We caught up with Pravesh Kumar MBE to explore the responsibility, emotion and urgency behind this work.

The Indian Army at the Palace marks a major moment: British South Asian artists telling British South Asian history on the very grounds where these soldiers once stood. What did it feel like to bring this story to Hampton Court Palace for the first time?

It was profoundly moving. To stand on the very ground where these Indian soldiers once stood and to have British South Asian artists tell their story in their own voices felt like history coming full circle. It was both a privilege and a homecoming.

You’ve spoken about the “immense responsibility” of honouring the 1.4 million Indian soldiers who fought for Britain. What was the most challenging part of ensuring their stories were told with both accuracy and emotional truth?

The hardest part was honouring the facts without losing the soul. These men were more than statistics – they were sons, friends, dreamers. Balancing historical rigour with a sense of their humanity required deep research, humility, and constant dialogue with community historians.

→ Readers interested in boundary-pushing creative voices can also explore our recent feature on Nathaniel Rackowe’s “Asphaltos Phos”, which examines light, space and urban memory in a completely different way.

Rifco has spent 25 years championing British South Asian stories. How does this production reflect the company’s mission – and how does it push it forward in a new way?

This production embodies our mission: giving voice to stories that have been overlooked for far too long. But it also steps into new territory, bringing untold British South Asian history directly into one of Britain’s most iconic heritage sites. It’s our past and our present meeting on equal footing.

The plays explore friendship, identity and belonging through a British South Asian lens. How did you balance the intimate human moments with the broader historical narrative when writing and directing these pieces?

I focused on the people first. History becomes meaningful when we feel it through lived experience. By grounding each play in personal moments—banter between soldiers, quiet fears, unexpected humour, the wider history becomes accessible, relatable and, ultimately, unforgettable.

This is the first time many audiences will hear these stories. What emotional response are you hoping visitors will carry with them after experiencing The Indian Army at the Palace?

I hope they leave with a sense of connection and recognition. For some, it will be pride; for others, surprise or reflection. Above all, I hope they feel that these stories belong firmly within British history and that they stay with them long after they’ve left the Palace.

You developed the stories alongside Sikh community historians and a cast of British South Asian artists, including Raxstar. How did this collaborative process shape the authenticity and tone of the final performances?

I think collaboration was essential. Our community curator historians, Tejpal Singh Ralmill and Rav Gill from Little History of Sikhs, brought depth and accuracy; our artists brought lived experience, nuance and cultural instinct. Working with talents like Raxstar created a production that feels rooted, contemporary and emotionally honest, an actual conversation between past and present with his beautiful poetic flow.

Instead of poppies, audiences are invited to wear marigolds—a powerful symbol across South Asia. How did you arrive at this choice, and what does the marigold represent in the context of remembrance?

The marigold is a flower of memory, celebration and resilience across South Asia. Choosing it allows communities to honour their ancestors in a culturally resonant way. It doesn’t replace the poppy – it complements it, offering a fuller, more inclusive language of remembrance.

As Rifco celebrates 25 years, you’ve built an extraordinary legacy of representation, community and cultural storytelling. Looking ahead, what kinds of stories do you feel British theatre still hasn’t made space for—and how do you hope to change that?

British theatre still has gaps, stories of migration, working-class British South Asian life, queer South Asian voices, and the everyday humour and struggle that shaped our families. We want to keep widening the lens, making space for narratives that are bold, joyful, complex and unapologetically ours. As the country feels increasingly divided, there is more that we share than divides us.