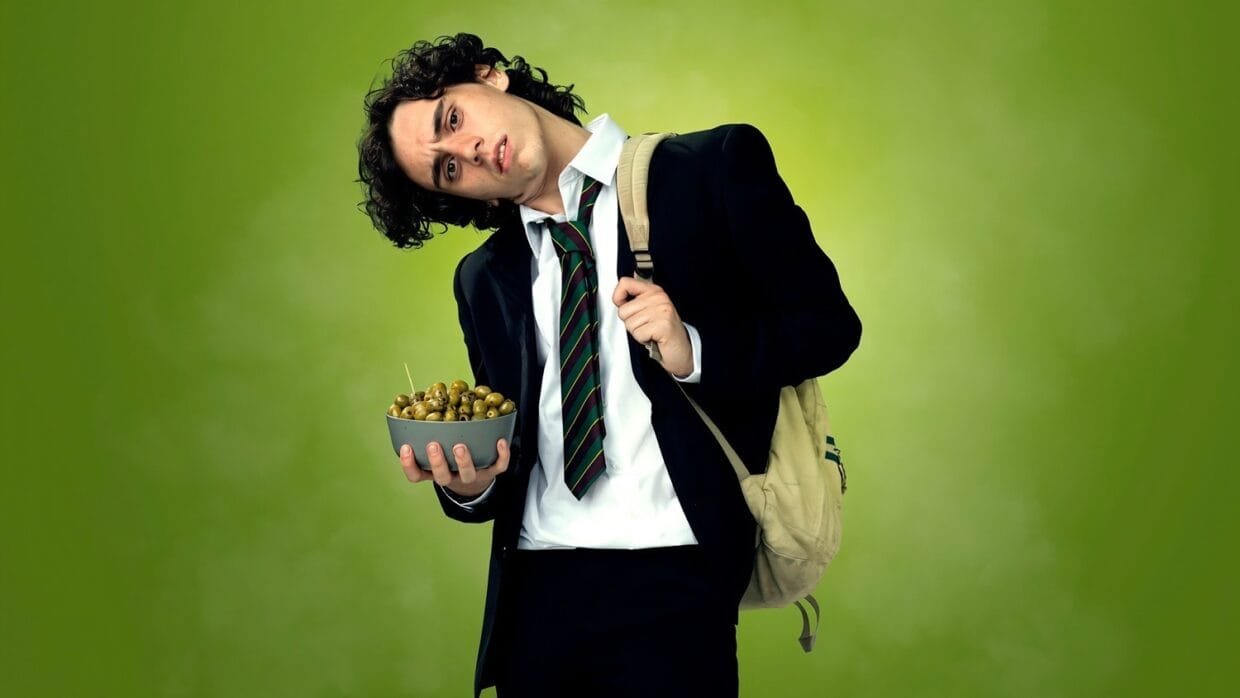

The Olive Boy is rooted in your own story — grief, adolescence, and the chaos of trying-to-grow-up while falling apart. What made you decide that now was the right time to tell it on stage?

The Olive Boy is a universal story. If we are lucky enough to live what most people would call a normal life, there are two experiences we are almost guaranteed to face: growing up and grief. Grief is something that society often struggles to talk about, and I was no different. I found it incredibly hard, especially during my adolescence. I wrote the show because, in a strange way, I knew it was time. I am a writer, and writers are always told to write what they know. At that point in my life, all I truly knew was grief, so it became the only thing I felt able to explore. There was never a conscious decision for the show to be as open and honest as it is, but once I started writing about my own experiences, I could not hold anything back. I found it hilarious to look back at the stupidity of myself as a fifteen year old boy, and healing to revisit the pain I once felt, especially now that I can see what I did not know then: that things were going to get better.

The play moves between dark comedy and devastating honesty. How did you find that balance — letting people laugh without ever trivialising what you lived through?

I think that teenage boys are, by nature, funny. They walk around believing they know everything while knowing almost nothing. Their priorities are the complete opposite of an adult’s in nearly every way, and it is very easy to laugh at that. If I am asking an audience to go on a journey led by a fifteen year old boy, then I have to accept that they will laugh at him. After all, he is ridiculous. I also believe that light and dark belong together. If we had never experienced light, we would never fear the dark. If the audience never laughs, then how could I expect them to cry?

You’ve said The Olive Boy is “a darkly comic coming-of-age story about grief and love.” How did turning personal loss into performance change the way you relate to those experiences?

Honestly, I didn’t. My grief feels exactly the same as it always did. Creating The Olive Boy has not made anything easier for me, but it has made me feel less alone. By sharing my story, other people feel able to share theirs with me. We talk. We cry. We hug. So even though I still carry the same feelings I have always carried, it helps to know that I am not going through them on my own.

The recorded therapist voice by Ronni Ancona adds a fascinating layer — distant, clinical, almost disembodied. What inspired that choice, and how does it reflect your own teenage experience of grief and therapy?

I remember that when I was writing the show, I reached the end but kept feeling that something important was missing. I could never quite work out what it was. Then, about four weeks before we were set to open, I suddenly had this idea to intercut parts of the story with a therapy scene, a single session that we would keep returning to. From the very beginning, it became our way of showing the audience that there was more to him than the Olive Boy was willing to say aloud.

Therapy, at least for me, was something I could barely admit to during my school years. Secondary school operates on its own strange hierarchy, almost like a battlefield where everyone is desperately trying to cement their place as the funniest, the toughest, the most desirable. In that environment, therapy is treated like a witness. I wanted to explore that within the show. Hence, why the scenes are always meant to feel like an interrogation.

When it comes to Ronni, she’s just amazing! I did a movie with her last year before asking her to jump on board this production as a favour. Of course, being the wonderful person she is, said yes.

Grief and masculinity have always had a complicated relationship. What have you learned about how young men process loss — and what do you hope audiences, especially men, take away from this story?

There are so many men who feel ashamed to cry, who are scared to admit when they feel sad. Even my closest male friends will cover their faces or rush off to the toilet when they need a moment, doing everything they can to hide a single tear. I think a lot of that comes from the constant fear of how we are being judged, especially by women, as if showing emotion somehow makes us less. I wanted to challenge that. I wanted to show that vulnerability is not weakness, it is courage. I cry in The Olive Boy every single night, in front of a room full of strangers, and not once has anyone looked down on me for it. So if people won’t look down on me for crying in a room full of strangers, why would they look down on you for crying in a room full of friends?

You first staged The Olive Boy at the Camden Fringe, then went on to Edinburgh, a UK tour, and now a dedicated London run at Southwark Playhouse. How has the show — and your relationship to it — evolved through that journey?

I am incredibly proud of this show. I never imagined in a million years that it would receive the response it has from audiences. I did not expect it to run for this long, and perhaps that is exactly why it has. Creating work like this is a real slog, from developing the piece to finding a producer, securing funding and convincing people to buy tickets. But it is always worth it. This show is something I am completely proud of, and I feel genuinely honoured to perform it. This run at Southwark may be it’s final run, ever, at least with it being performed by me. So I shall treasure every minute of it.

Director Scott Le Crass has a gift for bringing emotional precision to intimate stories. What has collaborating with him added to The Olive Boy and to you as a performer?

Working with Scott is an utter privilege, he took a big risk coming on board this show, not only as a director but as a producer. His mum also passed away young – so we have that in common. It’s truly special for two people to be in a room turning their pain into art. He’s also just a fantastic director and person. You work with Scott, never for him. I wish more directors out there were like him. He’s egoless yet extremely talented.

After The Olive Boy, what’s next? Do you think you’ll keep exploring personal storytelling, or are you tempted to step into something completely different next?

Every story I write will always be personal in some way, even if it does not seem that way on the surface. I think as a writer you naturally gravitate toward the things you feel connected to. Will I continue to write directly about my mum? No. But I will always write from the lessons she left me with. Whenever I start something new, whether it is a film, a series or a play, I always ask myself one question before anything else: Would Mum like this?