Interview with Michael Walling

Thirty years is a remarkable milestone for any theatre company. When you look back to Border Crossings’ beginnings in 1995, what do you remember most about the world and cultural landscape that inspired its creation?

My memories of the particular incidents that made me want to create the company don’t actually feel that different from the world we live in today. There have been a lot of changes, of course, but looking back I’m struck by the way many of the terrors of the present moment were already present in embryo.

There were two projects I worked on which led me towards Border Crossings. The first was ROMEO AND JULIET in West Coast America, where I cast one family as Black and the other as white, resulting in death threats to the young woman playing Juliet and myself – threats which the police demonstrated to be very real when they found the arms cache. That was very much a hint of what would become Trump’s MAGA movement.

The second was an invitation from Mahesh Dattani, who saw that R&J, to direct THE TEMPEST in India. The work in the States had made him think of the Hindu-Muslim tensions in his own country, and again that revealed underlying historical trends which have since led to Narendra Modi. One of the people I befriended during that formative time in India was the investigative journalist Gauri Lankesh, whose murder by right-wing thugs really brought home to me how dangerous a place India has become.

CHECKPOINT: 30 Years of Border Crossings isn’t just a celebration — it’s also an act of reimagining. How did you approach turning an archive of past work into something living, collaborative, and forward-looking?

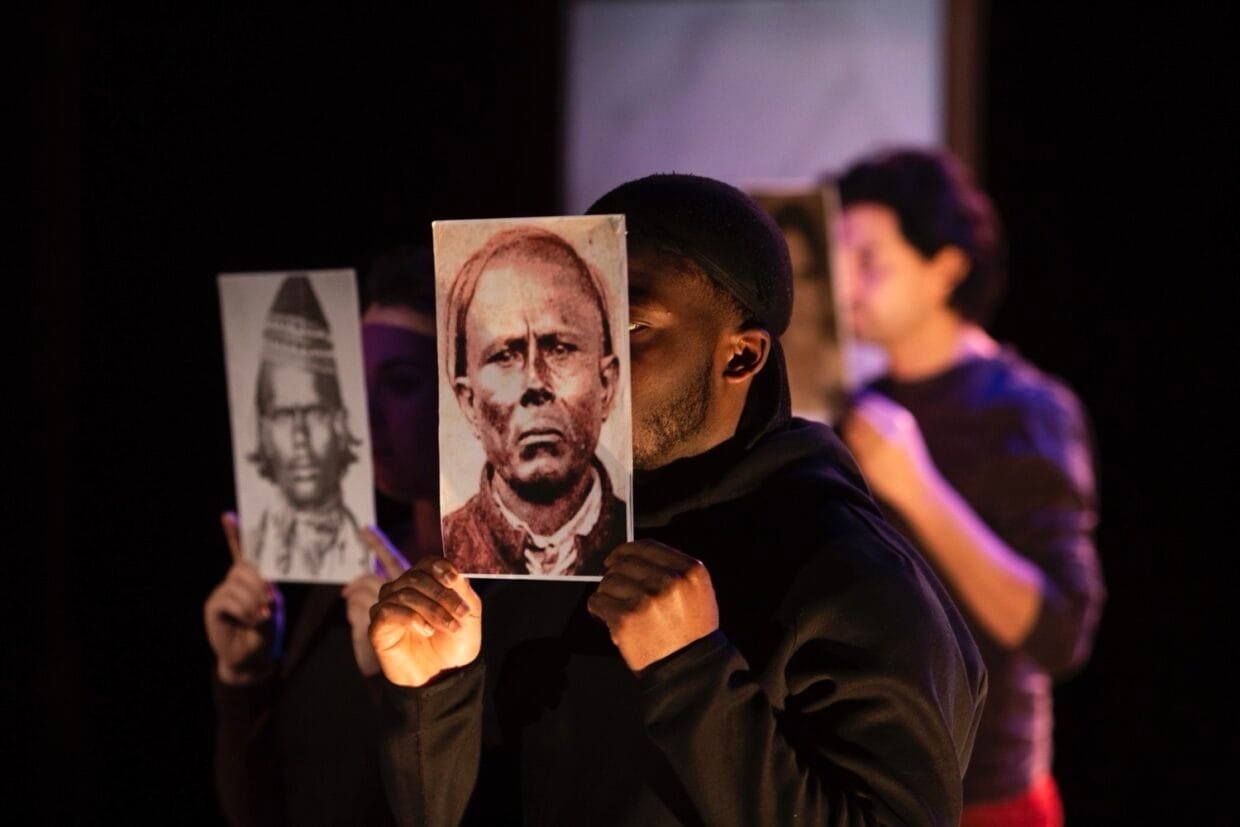

We’ve been working with schools and drama schools to explore what our past work might mean to younger generations today: I wanted to think of the heritage in terms of a legacy. In each case, we’ve offered the group three or four past projects to explore, showing them videos, giving them scripts, sharing articles, and whenever possible introducing them to people who were involved in the original process, particularly when those people come from cultures with which they may not be familiar.

Then it’s been over to the young people to find something in that experience that resonated with them, and to make their own short performance pieces in response. And of course they also come from a wide range of backgrounds, which really bears fruit in developing the intercultural journey.

→ Explore creative spaces in Shoreditch supporting youth voices.

The inclusion of school children creating new plays in response to Border Crossings’ archive feels particularly powerful. Why was youth participation such a key part of your vision for this event?

When an organisation reaches a milestone like 30 years, you have to start thinking about legacy. That doesn’t mean we’re intending to stop what we’re doing, but it does mean that we need to identify what’s central to the achievement to date, and to pass that on.

I’m often surprised when I work in educational settings just how little the curriculum has changed, even since I was at school. Theatre is still primarily seen in terms of literature, and actor training is still rooted in Stanislavsky. Our journey moved beyond that, and so where we’ve got to is where the next generation should be beginning.

Intercultural theatre has always been at the heart of Border Crossings. How has your understanding of “intercultural” evolved over three decades — and what does it mean in a world that feels more polarised than ever?

This is a massive and very important question. Back in the 1990s, intercultural theatre was largely understood in terms of a few famous directors (Brook, Barba, Schechner and in some ways Mnouchkine) who made aesthetic borrowings from other cultures, particularly Asian ones, in order to lend an impression of universality or spirituality to their work.

There were many aspects of what they did that I would still applaud, but I was always troubled by the ironing out of the real differences that existed between their actors, and the way in which “universal” actually came to mean lots of people from around the world conforming to a Western director’s vision.

We were one of the first organisations to attempt a more genuinely dialogic approach, with difference being emphasised and foregrounded rather than rejected. That took us towards a more politicised, post-colonial understanding of the world, and so towards a drama rooted in conflict but also in change.

I agree with you about the deep polarisation of the present moment. As I said at the start, the seeds of it were present even in the 90s, and we do need to understand these prejudices in historical terms. I think it’s one of our roles to make sense of what appears irrational, inviting people to see their own culture in relation to evolving narratives.

But of course that is in itself provocative to some sectors of our society. Just this week, when we announced our next project, SUPPLIANTS OF SYRIA, we received a torrent of racist obscenity and abuse on social media. This kind of invective represents a refusal of engagement. I think we have to find a way to bring a wider audience into the more open, nuanced and equal spaces that theatre can offer – but that’s primarily a political problem. Theatre and democracy are twin arms of a participatory, assembly-based approach to social cohesion. Because both have been turned into commodities and spaces for personal advancement, we have lost sight of true dialogue and genuine exchange.

You’ve said that not every global change in the last 30 years has been positive. How do you see theatre’s role in countering the resurgence of racism, division, and cultural isolationism?

I don’t think theatre can actually make political change – except for a few very specific examples. But what it can do is to change how people see the world they live in, how they understand it and so how they attempt to live in it. And that does make change happen, on a long-term basis.

But we have to take the long view. That’s what working with Indigenous people has taught me: look deep into your history, your culture, your heritage, and that past will help you to take the long view into the future, and imagine a world that you may never see but would wish to bequeath.

xxx

CHECKPOINT: 30 Years of Border Crossings takes place at Hoxton Hall on 28 November 2025.