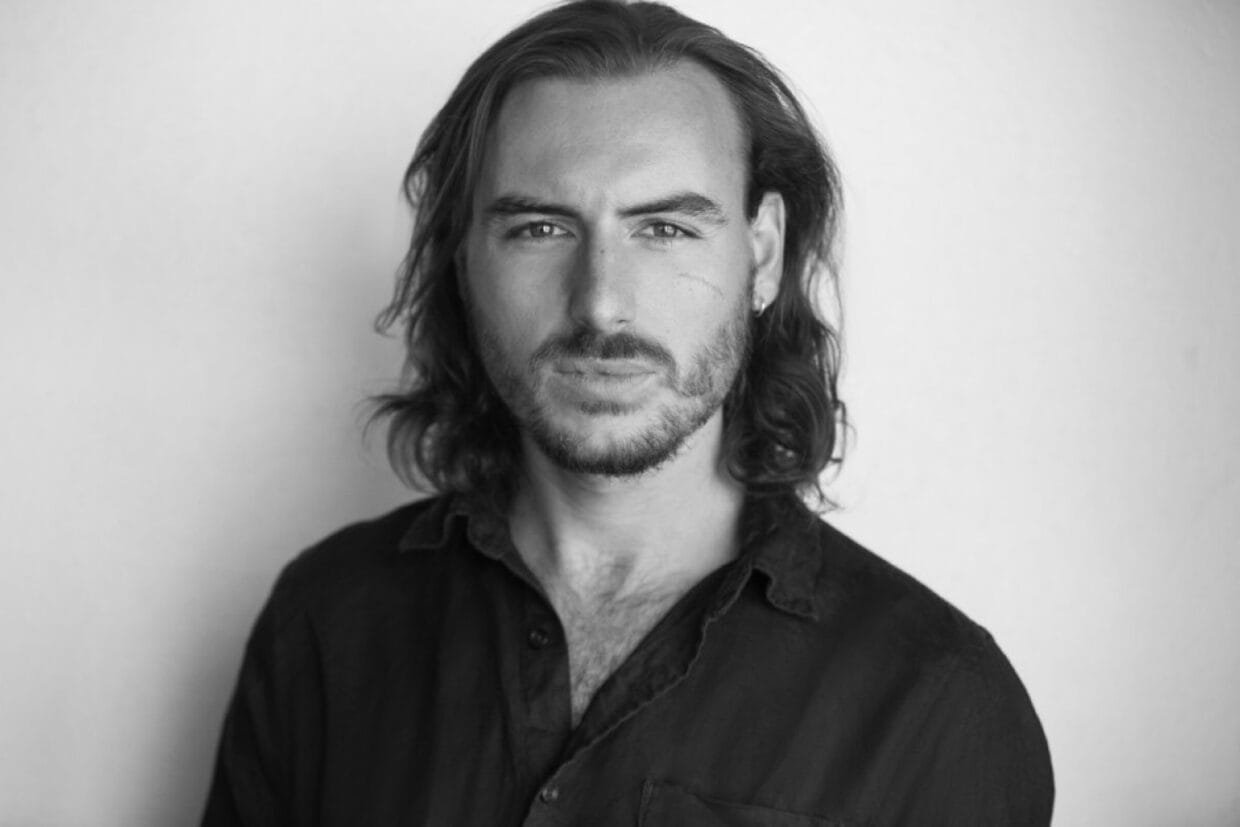

In an age where clout-chasing can be more dangerous than it looks, Jordan Murphy Doidge dives deep into the consequences of digital desperation with his haunting short film CLOUT. The film follows a lonely teen at an elite private school whose thirst for online fame leads him down a twisted path. Inspired by The Boy Who Cried Wolf and real conversations around youth, tech, and truth, the story unfolds as a cautionary tale with a sharp social edge. We caught up with Jordan Murphy Doidge to discuss storytelling, casting Archie Yates, and why it’s time we start listening to young people.

What initially sparked the idea for Clout?

The origins of CLOUT emerged after I became hyper aware of the damaging impact social media is having on today’s youth, especially my younger siblings. As the eldest in a large family, I witnessed first-hand how it took hold during lockdown. We began exploring how we could weave this into a modern fable that would resonate with a wide audience. We were drawn to The Boy Who Cried Wolf – it struck us as a powerful metaphor for the dark nature of social media.

How does the environment of the private school setting add to the film’s commentary on status and social validation?

We were very intentional in setting this story within a private school environment. There is often a cultural stigma attached to those who attend elite schools – perceptions of privilege, protection, and inherited advantage. We wanted to challenge these assumptions by telling a story that subverts and interrogates those ideologies, particularly around class and social hierarchy.

Despite his obvious flaws, Oskar is portrayed as deeply sympathetic. How did you approach crafting the character?

When developing Oskar, we wanted to create a relatable character grounded in the real-life challenges many young people face today. His parents are going through a divorce, he’s bullied at school, and struggles to fit in – so he escapes into elaborate stories as a way of feeling ‘seen’ – reminiscent of characters like Chunk from The Goonies – someone whose quirks and vulnerability make them instantly endearing.

The performances from the young cast feel authentic across the board, especially Archie Yates who portrays Oskar. How was your process for casting?

We had Archie in mind from the very beginning, having seen him in Jojo Rabbit. He brought such innocence and vulnerability – exactly what we needed for Oskar. For a cautionary tale to land, the audience needs someone they can truly root for. By chance, our casting director Georgia Topley had cast Jojo Rabbit, which made bringing Archie on board feel like fate. Georgia did a fantastic job pulling together the rest of the cast too. We workshopped the opening gaming scene and cast those who felt the most natural.

Once cast, we kicked off rehearsals a little differently – I took them to a haunted mansion escape room to help build some chemistry – they were instant best friends!

What was the greatest challenge during production and how did you overcome it?

It was a tricky shoot to get off the ground, mainly because of the setting. Convincing schools to host our story wasn’t easy, but after rallying support from alumni, we managed to secure Harrow School – which felt like a win in itself. We had three false starts and plenty of curveballs. One of the bigger challenges was persuading agents & parents that we were safely staging a drowning scene – not the easiest pitch.

In a strange twist of fate, my car broke down at Gatwick Airport and the lovely Chelsea Mather stopped to help. We got chatting, and it turned out she was a stunt performer just back from working on the latest Bond film. I told her about our project, we stayed in touch, and eight months later she was on set helping us shoot the final scene!

How has your personal relationship with film evolved over time, and how did that influence the narrative?

My love of cinema started early. Film has always been a big passion in my family – especially with my mum. We’ve had an annual Lord of the Rings marathon tradition for years now. Some of my earliest memories are of sneaking into double features with my dad, watching films far too graphic for my age. It felt thrilling, and sparked a lifelong love of film.

Every Friday, we’d rent two films – one studio, one foreign – and over time, that became a kind of informal film school. We explored everything from French and Korean cinema to Italian classics and Japanese anime. That mix built a really eclectic foundation, and I carry it into everything I do.

This love of global storytelling – across genres, cultures, and languages – deeply informs my work. For Clout, the team and I were obsessive in our prep, paying close attention to the thematic details: the production design, sound, and visual language were all crafted to reflect the narrative beats of the story.

In your view, what more can society do to protect young people from the darker aspects of social media?

There are many contributing factors, and it’s a much wider conversation – but big tech certainly plays a major role. What struck me most during the making of Clout was just how much young people have to say on the subject. We need to stop assuming we have all the answers and start listening to them more actively. Rather than relying solely on ‘professionals’ to lead the conversation, we should create more spaces where young people can share their own experiences openly. Communication is key – engaging with our communities and giving young people a platform is how we start to empower real change.

Do you have any plans for your next project?

I’ve learned a great deal through this narrative project – there’s a powerful energy that emerges through true collaboration. At our best, we’re all simply conduits, in service to the story. I firmly believe cinema is as vital to culture as politics – it gives voice to the people. That’s why I feel compelled to tell stories that explore social commentary, but through a lens of magical realism.

I’ve recently written a play titled Triage, which follows a young boy over the course of a night in an A&E waiting room. I plan to adapt it into an independent feature. The piece explores themes of addiction, abuse, and inequality, which gradually unfold into a ghost story.