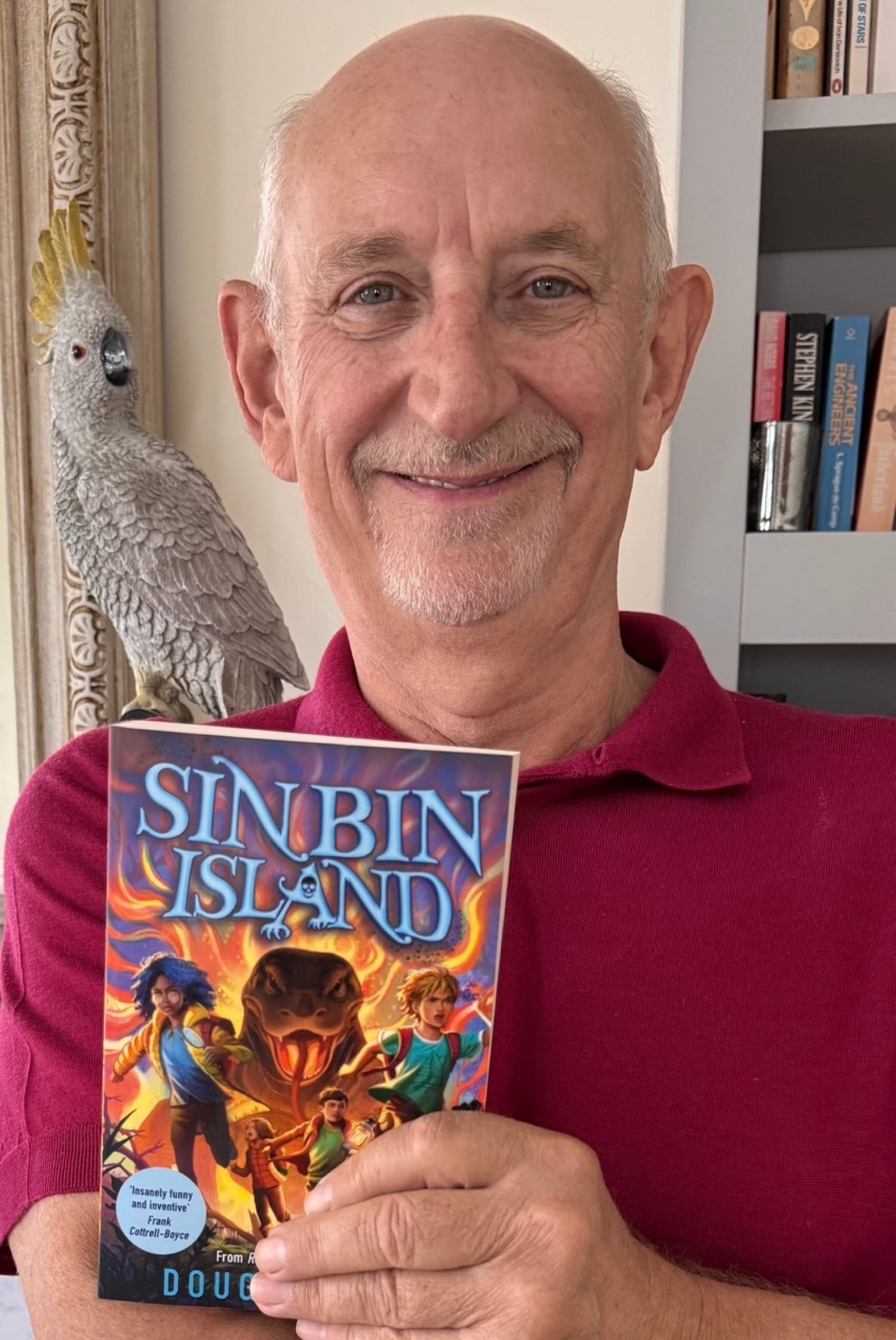

Doug Naylor, the Emmy-winning writer best known as co-creator of Red Dwarf, has turned his sharp wit toward a new audience. His debut children’s novel Sin Bin Island blends adventure, humour, and a touch of surrealism in the story of rebellious orphans, secret tunnels, and hidden treasure. It’s a bold move from one of British comedy’s most inventive storytellers, and one that has already won praise from the likes of Craig Charles. We caught up with Doug Naylor to talk about the inspirations, challenges, and future of his new literary journey.

Your debut children’s novel Sin Bin Island blends adventure, magic, and comedy. What inspired you to make the leap into children’s fiction?

I had an idea years ago for a kids’ adventure story about a flying saucer and wrote three x 45-minute episodes for a potential TV series. This was where I first wrote for Digs and Cav. It wasn’t made because I was told ‘No TV company would be interested in an expensive comedy drama for kids.’ I was also told to turn it into a novel and ‘then you’ll be able to sell it,’ but then Red Dwarf got rebooted on UKTV and although I’d started the novel, I didn’t finish it. A couple of years ago, I thought it was a shame no one had seen that story and decided to finish it. The flying saucer stuff was already written; I just needed somewhere secluded for the saucer to crash. How about an orphanage? No, I thought, people would still notice the saucer crashing. Somewhere even more remote – how about the school has an island where they send the four worst-behaved kids who must survive for a week on just bread and water. I was off! I started but had such fun writing how the kids got demerits, or lashes as they called them at Cyril Sniggs’, I’d suddenly written a third of the novel and hadn’t got to Sin Bin Island yet let alone the flying saucer crash. I discussed the story with my son, who is a comedy writer too, and he told me he liked the set-up but to drop the flying saucer and make it about smugglers and secret tunnels instead. ‘If I were a kid, I’d definitely read that version of the book,’ he said. He was right. I took a deep breath and cut the flying saucer section – forty thousand words – and started to write about smugglers and hidden treasure.

→ Read our interview with horror author Jeremy C. Shipp for insights into his chilling creative world.

Red Dwarf has such a cult following built on surreal humour. How did writing for younger readers change the way you approached comedy and storytelling?

I didn’t consciously change anything. Four flawed characters come together to form a team and eventually triumph. In many ways, that’s the same set-up as Red Dwarf. Replace science fiction with magic, and genetic mutants with smugglers, and write as many one-liners as you can. Also, there are advantages to writing a novel; there are no budget constraints. If I want a two-headed giant turtle, I can have one and don’t need to check, if we can afford it or worry that the CGI might look terrible. Another advantage of a novel is I’m allowed to write similes when writing descriptions, which you can’t do in a TV script which has to remain lean. One of my favourites in Sin Bin is the description of Mr Spurtle: ‘Mr Spurtle’s nose looked lost. It started off straight, then turned left then right then left again, his teeth look like a vandalised piano and he smelt so uniquely unpleasant that even the smelliest of French cheeses would not have wanted to sit next to him on a bus.’

The book is set around a foreboding orphanage and a mysterious island. What drew you to those classic adventure tropes as a foundation?

I’d never seen them done in quite the way I intended to do them. I went to a school that was a boarding school but had day boys too. It was founded in the 14th century and was full of wildly eccentric teachers. The chemistry teacher sent boys out to buy cigarettes for him and once told his class not to pick up sodium while picking it up himself and then frantically trying to shake it off his hand. Another teacher threw a desk at a boy, a boy was sent to hospital with a broken arm and had to walk there in his rugby boots. The Chemistry lab seemed to be constantly on fire and one punishment that was regularly meted out was cutting the school lawn with a pair of nail scissors. The PE teacher taught English for several terms until they found a qualified English teacher. He always used to give me the exact same mark for my compositions until I realised, he wasn’t reading them. So, then I used to regularly include swear words and totally unsuitable material and yes, I still got the same mark! A slightly off kilter school with eccentric teachers and rebellious school kids was something I knew I could write about. And a Pirate curriculum seemed quite logical given a privateer founded the orphanage.

Craig Charles called Sin Bin Island “the book I always wanted to read as a kid.” How did that kind of feedback shape your confidence in this new direction?

I’d finished the book by the time Craig read it. He read the bound proof version. I was confident at that point because various people, as well as family and friends had read it, and the feedback was incredibly positive. I’d told Craig I was writing a children’s novel and he’d said he’d love to read it. He called me a few hours after he’d got it to say he was half-way through and loving it. He called me again the following day to say he’d finished it and raved about it. It was clear from what he said this was not just an old friend being supportive and I was very buoyed by this as Craig is one of the funniest, most fiercely intelligent people I know.

Your career spans Spitting Image, Red Dwarf, bestselling novels, and now middle grade fiction. How do you reinvent your creative voice across such different mediums?

Once I’ve found the characters and the situation, the characters become collaborators. They tell you what they would do in any given situation.

Sin Bin Island isn’t just funny—it’s also full of intrigue and heart. What do you hope young readers take away from this story beyond the laughs?

I hope they take away the importance of thinking for yourself and the fact there’s no bigger treasure than great friendships.

You’ve written for characters as iconic as Lister and Rimmer. How different is it to build brand-new characters for an audience that’s discovering you for the first time?

You write and you rewrite, and you rewrite and you rewrite and each time the characters get a little more layered and as the writer, you get to know them and understand them a little bit more then you rewrite and you rewrite and you rewrite some more and then you’ve finally finished it and you go on holiday for a much deserved rest where you rewrite eight chapters on your phone and e mail them to your publisher and then they make the bound proof and your make a further 350 changes. After that it’s pretty straightforward.

Looking ahead, do you see Sin Bin Island as a one-off adventure, or could this be the start of a new series for children?

It is the start of a series. I’m working on Return to Sin Bin Island right now, and there’s another after that, and I hope there’ll be more after the first three. After all, the Binners still have six more treasure chests to find all of them packed with surprises.