Christopher M. Anthony’s debut feature HEAVYWEIGHT is a taut chamber piece about ambition, loyalty and the brutal psychology of competition. Fresh from a world premiere at Raindance and a British Urban Film Festival screening, the film pairs intimate performances with nerve-tightening craft. With Nicholas Pinnock, Jason Isaacs and Jordan Bolger leading the cast, Anthony trades knockouts for nuance and lands plenty. We caught up with Christopher M. Anthony for a deep dive into process, pressure and why this story hits harder than the ring—we did an interview.

Heavyweight has been described as a bold and psychological take on the sports drama. What first drew you to the world of boxing as the foundation for your debut feature?

Combat sports and martial arts were always a big part of my life growing up. I trained and fought in both amateur and professional MMA in my twenties. Many of my old training partners fought in large events such as UFC, PrideFC and Dream. I was always interested in the way that combat sports break the boundaries of class and wealth. All that matters is what happens in that ring or in that gym. The psychology of it, not only as a competitor preparing for an upcoming fight or just having the discipline to turn up to training and leave your troubles at the door always intrigued me. On a whim, I began penning the emotional and physical journey on the day of my last fight and realised that there may be a film in it. I had toyed with the idea of a film set in a very minimal setting and during lockdown, ‘Heavyweight’ was born.I can’t say for certain why I had decided to pick boxing over MMA and had access to both worlds, but I felt that there was something visually more interesting about seeing the former on screen.

→ Explore more voices for fresh perspectives on storytelling in Creatives & Creators interviews.

Rather than focusing solely on the physicality of boxing, the film delves into the mental and emotional toll of ambition. What interested you most about exploring that psychological side of competition?

People fight for different reasons. For some, they had to fight their whole lives and the affinity for the sport came from survival. For others, it was a way to overcome insecurities from their youth. To reassert themselves in adulthood. Perhaps to prove others, or themselves wrong. I had been through many of those feelings myself and kept them bottled up to the detriment of my own mental health. Combat sports helped me manage my feelings and take out my frustrations in a very safe environment. Over the years I saw how different teammates managed their confidence whether it be a small interclub fight or a huge stadium event being broadcast around the world. I learned about where people came from and why they were there. Every story was different but we were united by a love of the same sport and willingness to excel. Whether you were a stock broker, filmmaker or a bank robber, we supported each other in our sport. I had my own story and over the past twenty-six years I’ve learned about the stories of others. It felt like a perfect backdrop to make a film about boxing that wasn’t about boxing.

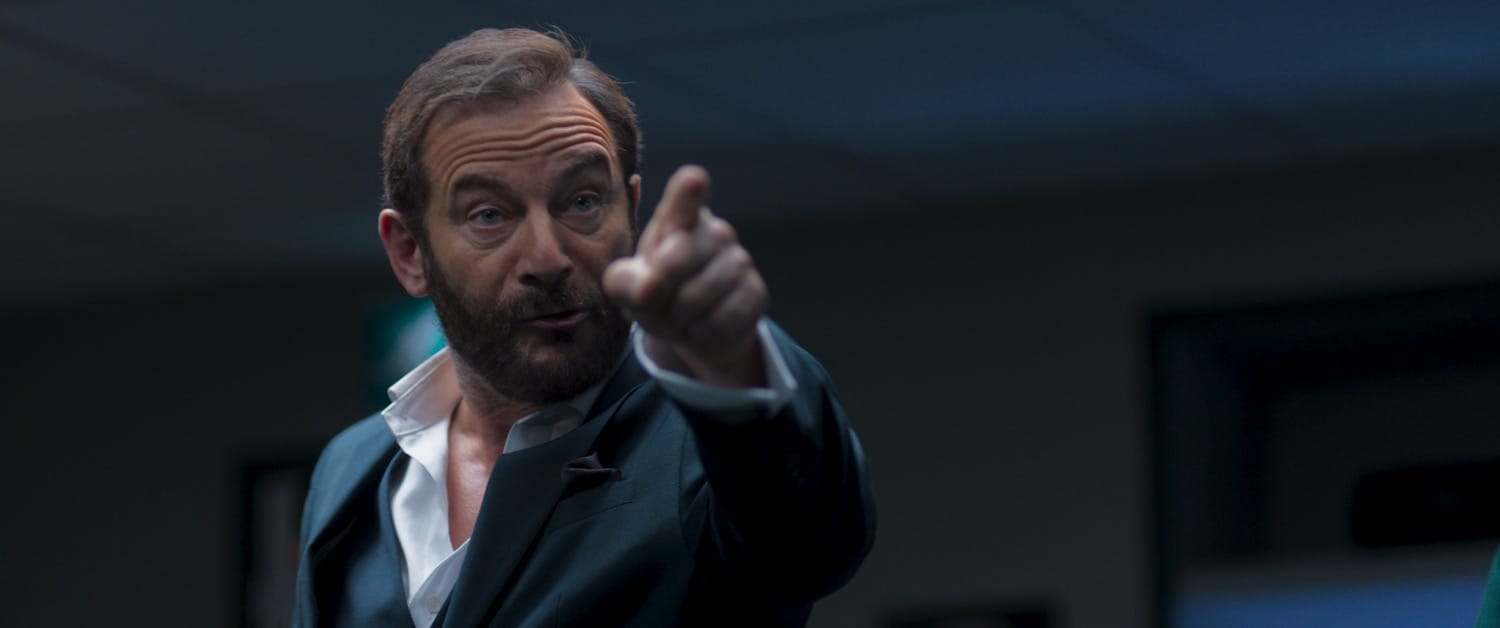

You’ve assembled an extraordinary cast — Nicholas Pinnock, Jason Isaacs, Jordan Bolger — all known for their depth and intensity. How did you approach working with them to bring such layered performances to life?

I was incredibly lucky to have assembled the cast I had. Making a film requires all the planets to align, only there are about a hundred planets in a filmmaker’s solar system. It’s not easy, and the actors’ strikes helped us with their availabilities. Over the numerous drafts of the script, I paired out the exposition little by little. It necessarily needed to be there in order for it to be removed. What is left is hopefully enough for an actor to convey in the classic ‘show don’t tell.’ Take out too much and the audience is left wondering. Take out too little and the audience feels like they are being spoon-fed. But then the actors have an amazing ability to bring all of that forward. As the director, I am there to guide them but it was very important for me to let them find their way and not tell them what they needed to do. I wanted them to find their way around both the material and the set and I always let them give me their first instinct. I would then give them guidance beyond that. As writer and director, I have the insight of the whole film and know when we are steering off course. I was also willing to learn about my own script. We had a few short days of rehearsal where the actors and I could workshop some key moments and I discovered things that I had written which I didn’t even realise how important they were until I saw it performed. That sort of feedback loop, and being able to feed that back to the actors and the crew is something that we can’t get from AI. It is unique to being in a room with people and feeding off each other’s energy and interpretations in order to create something better than you first intended. When you find those moments it gives the greatest satisfaction.

The film premiered at Raindance and now screens at the British Urban Film Festival — both important platforms for independent cinema. What has that journey been like, and how have audiences responded to the film so far?

It has been a long journey from day one of penning the first word during the pandemic to where it is now – being seen by audiences. Opening Raindance to a sold out Leicester Square cinema was a dream made better by winning Best Debut Director of a UK Feature. And screening at BUFF as well as taking home Best UK Feature was a great honour and a fantastic lead into the Awards Season. Independent cinema is the backbone of good storytelling. You can layer on all the VFX and action and giant sets but it still comes down to character and story. And that you can do on any scale. But the cinemas and the streamers want returns and believe that audiences won’t see small independent films. Yet we are currently watching huge films fail at the box office whilst the independent cinemas are still drawing crowds. When we first delivered the film, it felt like everyone loved it but no one wanted to take a punt on it. The industry is so risk averse that no one wants to make a move until someone else has made a move. And so many small, great films disappear as a result. Independent festivals such as Raindance and BUFF are vital to moving the dial. They are vital to recognising new talent and getting films in front of audiences. All it takes is that one right person that happens to be in the audience to recognise a film or a filmmaker, or one whisper or review to escape and set off a chain reaction. I am glad to say that the response has been incredible. I’ve had people connect to different aspects of the film. I’ve had people tell me they were in tears watching the film. I’ve had people connect themes in the film to their own experiences, sports, jobs and activities even though they are nowhere near the boxing world. We are now moving into the Awards race and hoping that the film will be further recognised. Who knows where this journey will end? As William Goldman says of the film industry in ‘Adventures In The Screen Trade,’ ‘nobody knows anything.’

Heavyweight feels both universal and deeply personal. Was there a moment or experience that sparked the idea for this story, or a connection that made it especially meaningful for you?

Steven Spielberg once said that making films was his therapy and having made ‘Heavyweight’ I entirely understand. Whilst Spielberg doesn’t write, you can see influences from his life and upbringing in many of his films. When I set out to write ‘Heavyweight’ I was adamant that I wouldn’t move into an overly dramatic narrative. It wouldn’t be a film about a boxer losing a fight for The Mob, for example. I soon realised that whilst I could give a literal telling of a boxer arriving at an arena until he goes out to fight. That film was about boxing but I didn’t want to make a film about boxing. There was a great opportunity to make something more and to really explore the human condition. Little by little I began introducing my own relationships into the characters. I began noticing interactions between characters were analogues of relationships between myself and members of my family, or friends. And because the relationships were real, it became easier to pen them. In some cases I didn’t even recognise some of the interactions had come from my life until months after the film was finished. I look back on some of those characters and behaviours and now I understand them, I feel that maybe I was a bit harsh, but I also felt that if these were real relationships for me, surely audiences would also connect to it. And it seems like they did. If this film helps others, then I hope that’s a good take away.

There’s a fine balance in the film between realism and stylisation — between the grit of the boxing world and the internal battles of its characters. How did you shape the visual and emotional tone of the film to reflect that tension?

The starting point of the script was always that there are a sequence of events that need to happen in the course of an evening of a boxer arriving until they step out. I did a heavy amount of research, calling on friends who have lived this life in the locker rooms of some of the biggest fights in history. I heard stories that were never heard beyond the doors of the locker rooms. I watched clips of champion boxers before the fights and not only did they inspire scenes in the film, I was able to ask about the truth behind many of them. What was the boxer and the team really thinking when that celebrity walked in? What was the mood before? What was the mood after? How did that affect the atmosphere in the room? One of the big changes was realising that Cain (played by Osy Ikhile) needed to be more than the character I had written. He was meant to be just someone from the opponent’s team that came to get into the head of Derek (Jordan Bolger) whilst supervising the handwrapping as happens in almost every fight. The lightbulb moment to make him Derek’s training partner, Adam’s (Nicholas Pinnock) student changed the entire dynamic of the second act and was inspired by something that actually happened to a friend of mine.

Whilst most of the tension was written into the script as a continuous piece that picks up momentum as it goes, we employed a number of editorial, audio and visual tricks to heighten the tension. Of course, a huge amount of credit must go to the cast who delivered incredible performances, and these tricks amplified them further. The language of the cinema changes and evolves throughout the film. Our BAFTA winning Cinematographer, Chas Appeti, kept a very subjective camera so we always felt like we were just another teammate in the room, watching as the chaos unfolds. When things are calm, we used a Trinity rig which gives gentle, long flowing moves as we float around the space. But we move to a handheld camera and fast cutting when things begin to fall apart. We subtly use audio tricks such as the Shepard Tone, commonly used by Christopher Nolan to provide discomfort. For a climactic scene where Adam and Derek are at odds and separated by a door, we had distinct sound design for each space. As the scene unfolds, we gently and imperceptibly steal elements of the sound from each side and move it to the other until it is one, indicating that they are back in tune with each other as fighter and coach. And then Andy Burrows’ (of Razorlight and Ricky Gervais’ ‘After Life’ fame) percussive score weaves seamlessly in with the sound design to further heighten the emotion.

As a debut feature filmmaker, what were the biggest creative challenges you faced — and what did the process teach you about yourself as a director?

We were on a tight budget, but I have learnt from years of making studio films as far back as the first Harry Potter, you never have enough time and enough money. But as cliched as it sounds, amazing creative things often come from making the most of challenging situations. And you will never be truly satisfied, as with any creative venture. I’ve learned to pick my battles and fight for the ones that are most important as you cannot win them all. It was a baptism of fire to direct an ensemble cast with long takes and scenes that last up to ten and twelve minutes. Actors have a different method of working and you have to be respectful of that. That is amplified a hundred-fold when we have eight or more actors in a scene. Letting the actors’ instinct come through and letting them try things even if they don’t work is really important. There has to be a mutual respect for there to be a positive outcome. Preparation is vital but always be open to discovering things in the moment. Originally coming from a background in VFX where we can correct and update things over days or even weeks, the pace of moving and being confident in your decisions as a director was perhaps the biggest challenge. Once you’ve moved on, you aren’t coming back. So you are constantly praying you made the right decision to move on, whilst also watching the producers who are staring at you as they tap their watches. This is but a small handful of things I learned and I am still learning.

Finally, with Heavyweight now entering BAFTA and BIFA consideration, what do you hope people take away from it — not just as a sports story, but as a portrait of what it means to fight, fail, and persevere?

That’s a great question. I would never tell an audience what to take away from a film. As with all artistic endeavours, it is purely subjective. I have my thoughts of the film I made but I have also been presented with views on scenes and characters that I had never even thought about. I find that exciting. They are not wrong. That is simply what they took from it and I’m okay with that. Equally the film has deliberately unanswered questions. As Tarantino says, if we give you the answers, the conversation ends. Because that becomes definitive. I also have seeded some ideas within the first act that perhaps change an audience’s thoughts on questions they may have after first viewing. Going in again with prior knowledge of what will happen, may give an audience a different perspective. On a more serious note, this is a film that discusses male mental health and subjectively includes notions of self-harm. We see particularly through the performances of Jordan Bolger and Osy Ikhile, vulnerabilities that we rarely see in real life. I hope that young people watching will see that behind the tough exteriors, we are all human and able to express and emote. That we all have self-doubt at times. That we all feel hurt and it is okay to show it. That sometimes the people we look up to are not infallible and they make mistakes. If this film allows the conversation of mental health to propagate and it inspires anyone who feels like they aren’t good enough to keep going, then it’s done something good. Few people see the failures it takes to be great but it is the person who persists through the difficulties and keeps going that is there to receive the success when it deservedly comes.