In Colour & Geometry, painter Paul McMichael distils a decade-plus journey from social realism to rigorous colour constructions, where grids, ratios and emotion share the same canvas. Rooted in Denis’s credo of a painting as ordered colour, his work draws lines between Renaissance proportion, De Stijl clarity and today’s visual noise. The result is a practice that treats colour as language and composition as score—precise, thoughtful and quietly bold. We caught up with Paul for a deep dive into process, proportion and why colour still speaks loudest—we did an interview.

Your exhibition Colour & Geometry spans over a decade of artistic evolution. How would you describe the journey from your early Social Realist works to your current explorations of abstraction and pure colour?

A natural evolutionary process involving critical self-reflection. I realised that I didn’t want to be constrained by literal subject matter after a while, or for that to be what spectators were looking at only in my paintings. I felt that this was getting in the way of my desire to express colour as a subject-in-itself; at the same time, I knew I wanted to apply paint to the canvas with order and structure. In this regard, underdrawing remained as the foundation of the process making composition an important part of my work also.

You mention that colour gradually became your “core motivation.” What is it about colour — rather than subject or form — that continues to captivate you as an artist?

Colour communicates more directly than subject or even form – this is what I am seeking to achieve with these paintings – direct communication. As an art lover, I am influenced by the tradition of artists from the Renaissance masters (Titian, Raphael, Veronese) onwards, who recognised and employed the role of colour to communicate information and ideas to the viewer. The symbolism of colour is primal. We all respond to colour from birth, whether we become interested in art or not. It’s all around us, naturally – a means of attracting for flowers or birds of paradise; as well as in manufactured commodities – products and advertising.

→ Explore more creative minds redefining the art scene in London.

Maurice Denis’s statement that a painting is “a flat surface covered with colours, put together in a certain order” seems central to your philosophy. How has this idea shaped your recent approach to composition and structure?

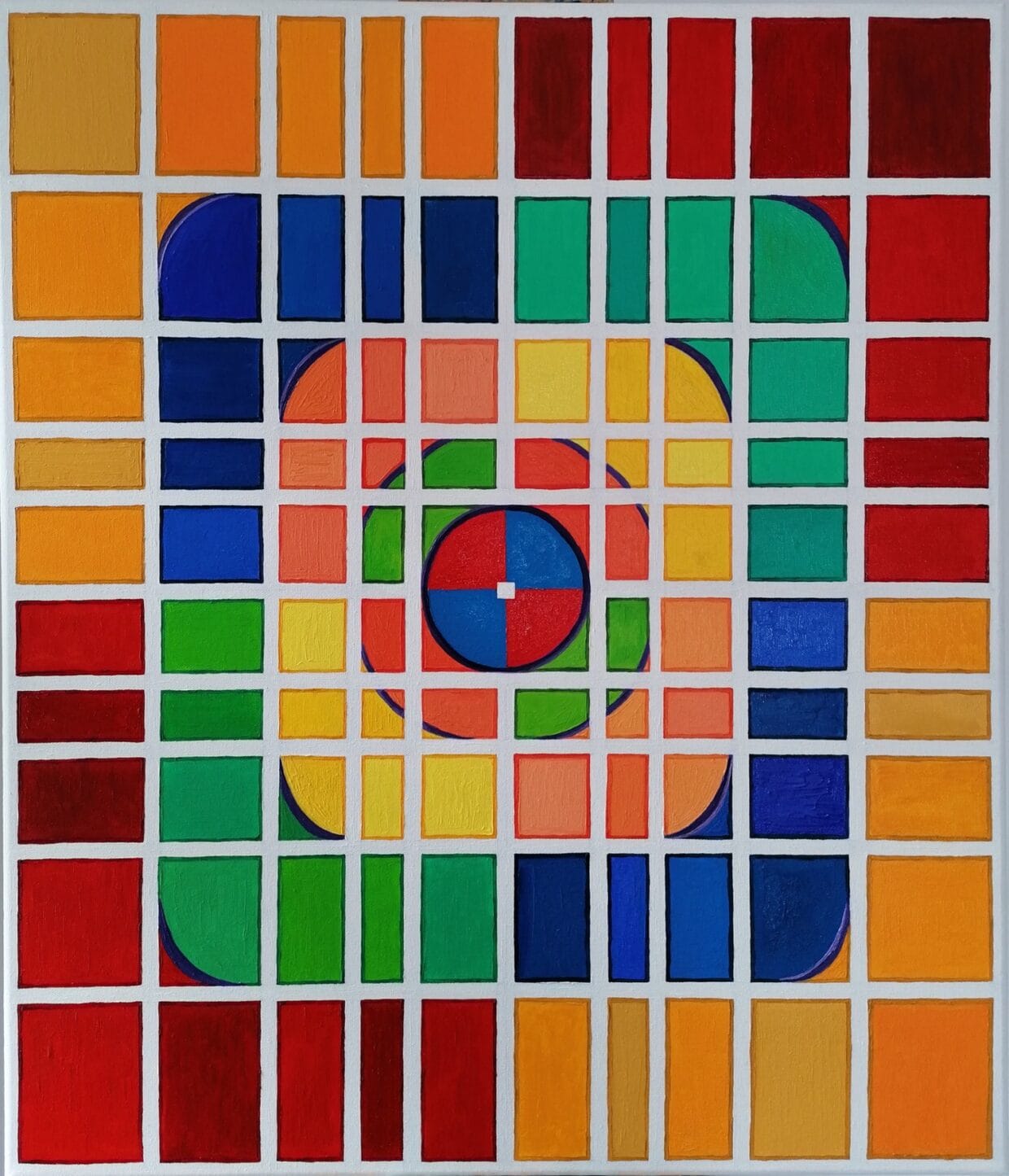

To begin with, I embraced Denis’s statement quite literally. When I used the term ‘Pure Painting’ for this series of works (2018 – 2024), I was following Denis’s definition ‘to the letter’. This helped me hone my own ideas of how I wanted to paint at this time – with simple, clear signs in pure colour on white grid/ ground – and the impact I wanted the work to have on the spectator, not just visually but affectively, stimulating both emotional and intellectual responses without dictating to anyone how to feel or what to think, specifically. An artist is working things out, like everyone else. Art is a process, never a complete representation of the world, therefore the artist is often working on instinct (and often getting it wrong). But we learn from failure as much as success.

Your Pure Painting series incorporates geometric grids and strict aesthetic principles of order, harmony, and proportion. How do you balance this sense of control with creative spontaneity in your work?

I don’t consider myself a ‘spontaneous creative’ in the Expressionist sense. Flinging paint on a canvas is not my method, although I admire the work of some of those who give vent to this urge! I am a thinker, an analyser, and someone who seeks order in a chaotic world. I think this comes across in my paintings.

Many of your recent pieces reference modernist movements like De Stijl, Cubism, and Suprematism. What do you find most relevant about these historical influences in today’s visual culture?

I believe in the application of mathematics and geometry in the creation of art and music like many of my predecessors and influences, from Leonardo’s studies of mathematical proportion (The Golden Section), Malevich’s atomistic Suprematism and Mondrian’s or Riley’s geometric harmonies to Bach, Schoenberg, Messiaen and Stockhausen in the musical realm, all of whom worked according to mathematical systems/ principles to produce their art. *The Golden Section (Section d’Or – Study #1) is the ‘subject’ of one of my paintings at the forthcoming exhibition at The Chapel Gallery. The ratio of 1: 1.618 is proven to be found in many natural forms, contributing a sense of order and visual appeal in the world which applies equally to human created works of art.

Another painting on display is titled Signorelli’s Floor, inspired by the National Gallery painting The Circumcision by the Renaissance artist, Luca Signorelli. I asked myself how could a Renaissance artist have been painting something as colourfully geometric as this, just as I am motivated to do similarly, 500 years ago. This is a rhetorical question of course – I can’t ask the artist to explain his work or thinking directly. I connect with Signorelli on some level and translate a similar conceptual idea to a modern situation. History is a circle, not a straight line. Everything gets re-interpreted and re-contextualised from a different stage of the historical process.

Your latest works appear to bridge abstraction and representation, moving between “real world motifs” and geometric reduction. What does this transitional phase reveal about where your practice is heading next?

As a ‘Socratic artist’ I tend more towards asking questions than answering them! All I can say is, I am never satisfied with where I am, so I am always in a ‘transitional phase’ in my work. One works at something until the idea is exhausted, then one experiments for a while until new ideas arise – a dialectical approach. Colour exploration still has a long way to go for me. I dream of the perfect ordering of colour harmony and proportion, and *The Golden Section doesn’t appear to have provided the definitive answer to my quest. So I can’t say if what I seek exists in the real world or only in my imagination. This is one reason why I am motivated to press on with the investigation, I suppose, and also why the ‘real world motif’ cannot be dismissed from the process entirely. Perhaps beauty is purely accidental and can only, at best, provide fleeting glimpses of truth. The artist must therefore be satisfied with attaining very occasional fleeting glimpses of the ultimate object.

You’ve spoken of “musical analogues” in your colour constructions. How do rhythm, harmony, or musicality inform the way you think about painting?

In my painting After Stockhausen – The Medium Is Code (Serial Square), I was addressing this very idea, of whether a painting could be as immediate as a musical composition, albeit one that presents as abstract: in coded form. Other artists have espoused musical connotations – Whistler’s ‘Nocturnes’; Kandinsky’s belief that colour is a synaesthetic phenomenon (evoking sound). I was exploring the connection between the system of a musical manuscript i.e. of a musical ‘language’ of notes on a stave to be ‘read’ by musicians and the analogue of colour and geometry as a similar language to be ‘read’ from the canvas. (Stockhausen had applied a serial method to some of his musical works based on Schoenberg’s 12-tone serialism).

More broadly, rhythm, harmony and musicality are concepts that an artist like me, who is as interested in music as I am painting, thinks about constantly as I work. Music affects the listener on a sensual/ emotional level immediately – can a painting do this analogously? One continues to seek a ‘formula’ for achieving this goal in the language of paint. (The poet Khlebnikov believed in the establishment of such a language as ‘the task of the artist’ – see exhibition quote).

After more than a decade of exhibitions across London, what does Colour & Geometry represent to you personally — and what do you hope visitors at St Margaret’s House take away from this new body of work?

Colour & Geometry represents the culmination of a first phase of this exploration. I subscribe to the motto ‘Never trust anyone who has a fully-formulated manifesto’ (artist or otherwise)! I hope that those who see the paintings will be affected in some way. To create art that makes viewers either think or feel something is what every artist seeks. We paint for ourselves, first and foremost, but definitely not ONLY for ourselves. That which is communicated is not a prescription – all language (including the language of painting) should be open to questioning, interpretation and be the basis for progressive dialogue, ideally.

xxx

Colour & Geometry by Paul McMichael

November 28-30th

The Chapel at St Margaret’s House,

21 Old Ford Road — E2 9PL